farmers markets

Vending for a day

My regular Saturday market stop two weeks ago ended with my pal and one of my favorite vendors, Norma Jean of Norma Jean’s Cuisine asking me to assist her the next week by managing her table while she handled a demo nearby.

So, this week I packed my bag for a 3-5 hour market trip which meant adding a gallon of water, bandanna, Florida water and my watch.

Since leaving Market Umbrella in 2011, I haven’t spent more than 2 hours behind a table as a manager or a vendor; I do help my pals Rob and Susie sell their baked goods when the line backs up since I often sit behind their table with them anyway, chatting about a million subjects, so stepping up to take the money or to bag items is the least I can do.

When I do consulting work with a market, I am there for a full day sometimes, but it is definitely a different vibe than managing or vending.This day, I was responsible for all of the sales at Norma’s table; no wandering off when I saw something to eat or see. Knowing the products well enough to answer questions easily and not in a rushed manner, keeping money straight, all had to be managed on my own.

I think every market manager and board member should step in and run a vendor table for an hour or two. It is important to watch the traffic, gauge the body language, note the questions of visitors and to get the vibe from that point of view.

Some thoughts from today:

1. It’s fascinating to me how many people were thrown by not seeing Norma. The products by themselves are not always enough to signal the same vendor. I think that is a great thing- the relationships between the shoppers and the vendors are meaningful and so the person-to-person connections are as important as we assert they are.

2. The number of new people, always: I think vendors and managers forget how many people are at the market for the first time. When I sensed someone new to the market by what they asked or how they moved through the market, I would ask them if they were a regular shopper and so heard from many first-timers. It shows how a market and its vendors need must be prepared to introduce their items and the system over and over and over again and not to assume that everyone knows their stuff or about the market. And this is a rural/suburban market and not an urban market and still has lots of newcomers.

3. Body language: Norma had left me a chair to sit in (I don’t think I’ve ever seen her sit in it actually) but I didn’t dare, having been trained at Market Umbrella that sitting at market for staff or volunteers was a no-no. It’s not that sometimes it isn’t okay; if the market is a tailgate market and right up against the table it can work (and look) well for a moment or two. However, those deep camp chairs that allow someone to sink down, I say no. But standing in place for so long was difficult for me; as a market manager, I had rarely stood in place for more than 5 minutes at a time and even had a rule to not engage in any conversation for more than 10 minutes. If needed,I would ask that person if I could call them to finish talking on Monday. Today, I found because I had to stand still so long, I had my hands on my hips regularly and so began to put them on the table or in my pockets or add busy work to stop doing it.

4. Even though many shoppers and all of the vendors know me and I am well acquainted with Norma’s products, I am even more of a true believer that employees are never going to equal with having the producer or their family standing there. The confidence in the products and the awareness of every step of the process is not at the same level. Add to that, how unlikely it is that any small feedback offered by shoppers or visitors will translate into action if it is given to an employee. Or, if slow sales of any one item is due to the lack of interest from shoppers or lack of sales technique of the employee. So even if markets allow employees to sell (which is quite necessary for most), I recommend that they add a rule that the producer has to sell at least once every month or two.

5. I love watching and being part of the barter of the market. As many of us know, many vendors barter their goods rather than exchange currency and to see the regular versions of that; Norma gets gluten-free bread for the vegan pesto samples in exchange for her items, and to be “paid” in those goods too helps remind me that we still are not measuring the true number of transactions at a market. Norma also has a barter system with one customer who has a credit slip at her booth-no one else is afforded that system, but I certainly have seen other vendors do that with some of their skilled neighbors as well.

6. How necessary it is for market staff or volunteers to roam the market regularly. So often, vendors get too busy to take a bathroom break or get change or need something and are stuck until someone happens by to assist. Lucky for me, Norma was within eyeshot as needed, and the sister managers Jan and Ann rolled by and connected with me once or twice. Checking in with your vendors can elevate the trust and raise the spirits of a market struggling in other ways.

7. When Norma finished her demo and sales earlier than expected, she cleaned up there and took over at her table, sending me on my way with warm thanks and gifts of food. As I got in my truck, I thought of how I get to finish my day there and then and not continue to sell, to then have to pack up/clean up, count the money to see if any profit has been made, and to make decisions for next week, next month etc. That long day and the added worry when the day is mediocre or bad has to be frightening and/or demoralizing to even the most confident producer. For many of our vendors, they have work for mid-week markets to start by mid-afternoon after market or the next morning or for some, to get a little rest for their other full-time job come Monday morning. My hat is off to those who believe enough in artisanal food or products to spend their life producing them for us.

8. What an enjoyable day.

The Edible South-Book Review

While checking out the local/regional shelves at Lemuria Books in Jackson MS (yes you need to stop in there if you are a booklover. And if you live around Jackson, I might even suggest a nice trip one hot weekend to spend a half day in the bookstore, some time in the Fondren co-op and maybe a stroll through Eudora Welty’s garden), I spotted this large book facing out, published last year but one that I had not heard of previously. The title was underwhelming, but the subtitle did intrigue me, as did the identification of it being the same author as Matzoh Ball Gumbo, which I had read and appreciated.

The book is broken into 3 sections: antebellum and post antebellum Southern food (“Plantation South”), late 19th c/ early 20th c (“New South”) and post 1950 (“modern South”), which is a very useful way to think about food and folkways in any American region actually. Each section has fascinating information about growing food or cuisine and uses scads of citations from prior research and popular books to showcase each.

The author, Marcie Cohen Ferris is a professor of American studies at UNC Chapel Hill and is well known among local food activists across the South. She has taken a wide view of Southern food since Jamestown days, using a great many of our most respected scholars work to weave a compelling and absorbing narrative. What is tricky about the long history here is the need to address earlier inaccuracies and overt racism embedded in some of that scholarship. The author does a deft job addressing those shortcomings without deleting what is useful from her predecessors’ work.

The Plantation South section was less comprehensive than I had hoped, especially knowing the beginnings of my own region around New Orleans as a tobacco company for the French, which has led to a commodity and export agricultural system that extends to this day. I had hoped for more about that era and more details of the enslaved and forced labor system of the Southern agriculture system, but it is quite likely that the scholarship was just not there to use.

The New South section should be required reading for any researcher or embedded activist working in the South. The founding of the Extension Service, of the home economics and demonstration movement and the research into healthy foods to reduce diet-based illnesses across the impoverished South are examples of the rich tapestry Cohen Ferris does explore and, for my money, is the best part of the book. Many times, I found myself referring to the notes and bibliography to record the name of the book she refers to in the section. Additionally, I much appreciated the section on Old Southern Tearooms and the account of the deliberate development at the turn of the 20th c of the myth of the genteel South, where a “southern narrative of abundance, skilled black cooks, loyal servants and generous hospitality of gracious planters and their wives” was displayed at places like Colonial Williamsburg, Charleston and of course New Orleans and as a result was completely accepted as the true story of a much more complicated and less romantic time. I certainly hope that her detailed work here separating fact from fiction may help put these embellished or completely fabricated stories of the “old South” in their proper place.

The Modern South section adds history on civil rights (how does it relate to food you say? lunch counter sit-ins, men’s-only lunch rooms anyone?), and history on federal programs like national school lunch program which are thoughtfully offered. The pieces on organizing natural food coops and buying clubs were so very welcome as little is available in popular research about how important these efforts were to the beginnings of the current local food/farmers markets) movement happening today. That leads to my main disappointment with the book – the scarce information on the farmers market/community garden movement of the 1970s-1990s, much less over the last 25 years which has been a dizzying and somewhat gratifying time for food sovereignty work. I can understand how the author was able to extract more from the researchers and writers of the Southern food system who focused on home cooking rather than to the (largely) nameless and transient activists and ideas of those same systems, but still, much has been written in the last 45 years not covered here. I can only hope for another book from this author that has the same level of detail, covering the last era from a grassroots or even a policy point of view. In any case, as I told a market leader in one of those vibrant places of local food in the South, this book is definitely a keeper and one destined to be used extensively among researchers, activists and policy makers.

View all my reviews

FMC’s SNAP EBT Equipment Program is Open

The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) Food and Nutrition Service (FNS) has partnered with the Farmers Market Coalition (FMC) to provide eligible farmers markets and direct marketing farmers with electronic benefit transfer (EBT) equipment necessary to process Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits.

WHAT

FMC will cover the costs of purchasing or renting SNAP EBT equipment and services (set-up costs, monthly service fees, and wireless fees) for up to three years. After their application has been approved, eligible farmers and farmers markets will choose their own SNAP EBT service provider from a list of participating companies. Transaction fees (for SNAP EBT, credit, and debit payments) will not be covered.

WHEN

The application is now open. This is a first-come, first-serve opportunity, which will be over when all the funds have been allocated.

WHO

SNAP-authorized farmers markets and direct marketing farmers (who sell at one or more farmers markets) are eligible for funding if they became authorized before Nov. 18, 2011, AND fall into one of the following categories:

They do not currently possess functioning EBT equipment;

OR They currently possess functioning EBT equipment, but received that equipment before May 2, 2012.

Wondering what qualifies as ‘not currently possessing functioning EBT equipment?’ Markets and farmers do not currently possess functioning EBT equipment if:

They currently rely on manual/paper vouchers to accept SNAP,

They do not currently accept SNAP and have never possessed functioning SNAP EBT equipment,

-OR-

They do not currently accept SNAP because their EBT equipment is :

Damaged beyond repair.

Non-operational because their SNAP EBT service provider no longer offers SNAP EBT processing in their state.

Stolen or lost.

For more information on the program, including frequently asked questions, an eligibility chart, background information and application instructions, visit HERE.

Make It, Grow It, Sell It – Whole Green Heart

FYI: this program is being offered by someone who has experience vending at farmers markets

A Home-Study Program for Building a Rewarding, Successful and Profitable Business Selling at Farmers Markets

For vendors, one of the key messages that we have found helps them grow their businesses is that it takes a combination of production expertise and business expertise to really be successful in the farmers’ market sector. I ran an organic herb farm, selling at farmers’ markets, for 18 years. I also managed a farmers’ market for 6 years, and because I come from an adult education background, I’ve been training other vendors and managers in our province since 2011 as the Director of Training for Farmers’ Markets of Nova Scotia. I speak at farmers’ market and organic agriculture conferences around North America and have learned even more from this rich interaction with so many other passionate, thoughtful people in various roles across our sector. For vendors, one of the key messages that we have found helps them grow their businesses is that it takes a combination of production expertise and business expertise to really be successful in the farmers’ market sector. I am launching a new home-study program for farmers’ market vendors.”

Big Data and Little Farmers Markets, Part 3

I used these examples in Part 2 of this series, but wanted to use them again for this post. To review:

Market A (which runs on Saturday morning downtown) is asked by its city to participate in a traffic planning project that will offer recommendations for car-free weekend days in the city center. The city will also review the requirement for parking lots in every new downtown development and possibly recalibrate where parking meters are located. To do this, the city will add driving strips to the areas around the market to count the cars and will monitor the meters and parking lot uses over the weekend. The market is being asked for its farmers to track their driving for all trips to the city and ask shoppers to do Dot Surveys on their driving experiences to the market on the weekend. Public transportation use will be gathered by university students.

Market B is partnering with an agricultural organization and other environmental organizations to measure the level of knowledge and awareness about farming in the greater metropolitan area. For one summer month, the market and other organizations will ask their supporters and farmers to use the hashtag #Junefarminfo on social media to share any news about markets, farm visits, gardening data or any other seasonal agricultural news.

Market C is working with its Main Street stores to understand shopping patterns by gathering data on average sales for credit and debit users. The Chamber of Commerce will also set up observation stations at key intersections to monitor Main Street shopper behavior such as where they congregate.

Market D has a grant with a health care corporation to offer incentives and will ask those voucher users to track their personal health care stats and their purchase and consumption of fresh foods. The users will get digital tools such as cameras to record their meals, voice recorders to record their children’s opinions about the menus (to upload on an online log) with their health stats such as BP, exercise regimen. That data will be compared to the larger Census population.

So all those ideas show how markets and their partners might be able to begin to use the world of Big Data. In those examples, one can see how the market benefits from having data that is (mostly) collected without a lot of work on the market’s part and yet is useful for them and for the larger community that the market also serves.

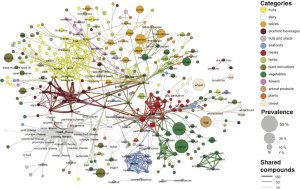

However, one of the best ways that markets can benefit from Big Data is slightly closer to home and even more useful to the stability and growth of the market itself. That is: to analyze and map the networks that markets foster and maintain, which is also known as network theory.

Network theory is a relatively new science that rose to prominence in the 1980s and 1990s and is about exploring and defining the relationships that a person or a community has and how, through their influence, their behavior is altered. What’s especially exciting about this work is that it combines many disciplines from mathematics to economics to social sciences.

A social network perspective can mean that data about relationships between the individuals can be as useful as the data about individuals themselves. Some people talk about this work in terms of strong ties and weak ties. Strong ties are the close relationships that we use with greater frequency and offer support and weak ties are those acquaintances who offer new information and connect us to other networks. The key is that in order to really understand a network, it is important to analyze the behavior of any member of the network in relation to other members action. This has a lot to do with incentives, which is obviously something markets have a lot of interest in.

From the book Networks, Crowds, and Markets: Reasoning about a Highly Connected World.

By David Easley and Jon Kleinberg. Cambridge University Press, 2010.

Complete preprint on-line at http://www.cs.cornell.edu/home/kleinber/networks-book/

I could go on and on about different theories and updates and critiques on these ideas, but the point to make here is this is science that is so very useful to the type of networks that food systems are propagating. Almost all of the work that farmers markets do rely on network theory without directly ascribing to it.

Think about a typical market day: a market could map each vendors booth to understand what people come to each table, using Dot Surveys or intercept surveys. That data could assist the vendor and the market. The market will benefit in knowing which are the anchor vendors of the market, which vendors constantly attract new shoppers, which vendors share shoppers etc. The market could also find out who among their shoppers bring information and ideas into the market and who carrries them out to the larger world from the market. All of this data would be mapped visually and would allow the market to be strategic with its efforts, connecting the appropriate type of shoppers to the vendors, expanding the product list for the shoppers likely to purchase new goods and so on.

Network theory would be quite beneficial to markets in their work to expand the reach to benefit program users and in the use of incentives. Since these market pilots began around 2005/2006, it has been a struggle to understand how to create a regular, return user of markets among those who have many barriers to adding this style of health and civic engagement. Those early markets created campaigns designed to offer the multiple and unique benefits of markets as a reason for benefit program shoppers to spend their few dollars there. Those markets also worked to reduce the barriers whenever possible by working with agencies on providing shuttles, offering activities for children while shopping, and adding non-traditional hours and locations for markets. Those efforts in New York, Arizona, California, Maryland, Massachusetts and Louisiana (among others) were positive but the early results were very small, attracting only a few of the shoppers desired. When the outcomes were analyzed by those organizations, it seemed that a few issues were cropping up again and again:

1. The agency that distributed the news of these market programs didn’t understand markets or did not have a relationship of trust with their clients that encouraged introduction of new ideas or acceptance of advice in changing their habits.

2. The market itself was not ready to welcome new benefit program shoppers- too few items were available or the market was not always welcoming to new shoppers who required extra steps and new payment systems.

3. Targeting the right group of “early adopters” among the large benefit program shopping base was impossible to decipher.

4. Some barriers remained and were too large for markets alone to address (lack of transportation or distance for example).

4. Finding the time for staff to do all of that work.

Over time, markets did their best to address these concerns, which has led to the expansion of these systems into every state and a combined impact in the millions for SNAP purchases at markets alone. The cash incentives assisted a great deal, especially with #2 and #4. However, this work would be made so much easier and the impact so much larger if network theory was applied.

Consider:

Market A is going to add a centralized card processing system and has funds to offer a cash incentive. But how to spend it? And how to prepare the market for the program?

If the market joined forces with a public health agency and a social science research team from a nearby university, it might begin by mapping the networks in that market to understand the strong and weak ties it contains as well as the structural holes in its network. It might find out that its vendors attract few new shoppers regularly or that the market’s staff is not connected to many outside actors in the larger network, thereby reducing the chance for information to flow.

It might also see that younger shoppers are not coming to the market and therefore conclude that focusing its efforts on attracting older benefit program shoppers (especially at first) might be a strategic move. If the market has a great many low-income shoppers using FMNP coupons already, the mapping of those shoppers may offer much data about how the market supports benefit program shoppers already and how it might expand with an audience already at market

The public health agency might do the same mapping for the agencies that are meant to offer the news of the market’s program. That mapping might find certain agencies or centers are better at introducing new ideas or have a population that is aligned already with the market’s demographic and therefore likely to feel welcomed.

As for incentives, what markets and their partners routinely tell me is more money is not always the answer. Not knowing what is expected from the use of the incentives or how to reach the best audience for that incentive is exhausting them or at least, puzzling them.

If markets knew their networks and knew where the holes were, they could use their incentive dollars much more efficiently and run their markets without burning out their staff or partners.

They might offer different incentives for their different locations, based on the barriers or offerings for each location. (They may also offer incentives to their vendors to test out new crops.)

If connectors are seen in large numbers in a market, then a “bring a friend” incentive might be offered, or if the mapping shows a large number of families entering the system in that area, then an incentive for a family level shopping experience may be useful.

One of the most important hypotheses that markets should use in their incentive strategy is how can they create a regular shopper through the use of the incentive. Of course, it is not the only hypothesis for a market; a large flagship market might identify their role as introducing new shoppers to their markets every month and use their funds to do just that. But for many markets with limited staff and small populations in and around the market, a never-ending cycle of new shoppers coming in for a few months and then not returning may not be the most efficient way to spend those dollars or their time. So this is also where network theory could be helpful.

By asking those using their EBT card to tell in detail where and how they heard about the program and by also tracking the number of visits they have after their introduction, we could begin to see which introductions work the best. Or by asking a small group of new EBT shoppers to be members of a long-term shopping focus group to track what happens during their visit (how many vendors they purchase from and how long they stay) and after (see Market D example at the top), we could learn about what EBT shoppers in that area value in their market experience. We may also find out that the market has few long-term return shoppers from the EBT population or we may find out that connectors become easy to spot and therefore they can be rewarded when sharing information on the market’s behalf.

In all of these cases, it will be easier for the staff to know what to do and when to do it if they understand their networks both in and around the market.

And of course, mapping the larger food systems around the markets’ systems would be exciting and could move policy issues to action sooner and allow funding to be increased for initiatives to fill the holes found.

However markets do it, what seems necessary is to know specifically who is using markets and how and why they decided to begin to use them and to whom those folks are connected. Network theory can be the best and widest use of the world of Big Data, especially to accomplish what Farmers Market Coalition has set as their call to action: that markets are for everyone.

Some reading, if you are interested:

http://www.foodsystemnetworks.org

http://gladwell.com/the-tipping-point

Reclaiming, Relocalizing, Reconnecting: The Power of Taking Back Local Food Systems

A rare Wednesday post on the 45th anniversary of Earth Day.

A new report by Friends of the Earth Europe looks at five examples of European communities successfully taking on the challenge of creating new systems that honor wise stewardship, local wealth and health and civic engagement. Its an inspiring report; share it widely.

.

Crossroads Community Food Network video

Great video from Crossroads Community Food Network, which runs the wonderful Crossroads Farmers Market in Takoma Park Maryland. It produced by the daughter of one of their board members as a Spanish project for high school.

Just shows what kind of smart and inclusive outreach can be done by community members when they are encouraged.

FINI programs funded for FY 2015/2016

Congratulations!

USDA is funding projects in 26 states for up to 4 years, using funds from FY2014 and FY2015. USDA will issue a separate request for applications in FY16, and in subsequent years. Fiscal year 2014 and 2015 awards are:

Pilot projects (up to $100,000, not to exceed 1 year):

Yolo County Department of Employment and Social Services, Woodland, Calif., $100,000

Heritage Ranch, Inc., Honaunau, Hawaii, $100,000

Backyard Harvest, Inc., Moscow, Idaho, $10,695

City of Aurora, Aurora, Ill., $30,000

Forsyth Farmers’ Market, Inc., Savannah, Ga., $50,000

Blue Grass Community Foundation, Lexington, Ky., $47,250

Lower Phalen Creek Project, Saint Paul, Minn., $45,230

Vermont Farm-to-School, Inc., Newport, V.T., $93,750

New Mexico Farmers Marketing Association, Santa Fe, N.M., $99,999

Santa Fe Community Foundation, Santa Fe, N.M., $100,000

Guilford County Department of Health and Human Services, Greensboro, N.C., $99,987

Chester County Food Bank, Exton, Pa., $76,543

Nurture Nature Center, Easton, Pa., $56,918

Rodale Institute, Kutztown, Pa., $46,442

Rhode Island Public Health Institute, Providence, R.I., $100,000

San Antonio Food Bank, San Antonio, Texas, $100,000

Multi-year community-based projects (up to $500,000, not to exceed 4 years):

Mandela Marketplace, Inc., Oakland, Calif., $422,500

Market Umbrella, New Orleans, La., $378,326

Maine Farmland Trust, Belfast, Maine, $249,816

Farmers Market Fund, Portland, Ore., $499,172

The Food Trust, Philadelphia, Pa., $500,000

Utahns Against Hunger, Salt Lake City, Utah, $247,038

Opportunity Council, Bellingham, Wash., $301,658

Multi-year large-scale projects ($500,000 or greater, not to exceed 4 years):

Ecology Center, Berkeley, Calif., $3,704,287

Wholesome Wave Foundation Charitable Ventures, Inc., Bridgeport, Conn., $3,775,700

AARP Foundation, Washington, D.C., $3,306,224

Florida Certified Organic Growers and Consumers, Gainesville, Fla., $1,937,179

Massachusetts Department of Transitional Assistance, Boston, Mass., $3,401,384

Fair Food Network, Ann Arbor, Mich., $5,171,779

International Rescue Committee, Inc., New York, N.Y., $564,231

Washington State Department of Health, Tumwater, Wash., $5,859,307

Descriptions of the funded projects are available on the NIFA website.

Farmers Market Metrics May Be Coming To Your Town

This is a reprint of a blog that I wrote for the Farmers Market Metrics page on Farmers Market Coalition’s site. There is a growing need for food and civic systems evaluation that is designed and implemented in partnership with the grassroots organization and uses contextual and disciplined metrics that are useful to that organization and to their partners. The new pilots and research happening at FMC and their partners, such as University of Wisconsin-Madison, are hoping to address that need.

ecocities emerging

Grant season has begun

I wish everyone good luck with their proposals and hope that my readers know if I can be of assistance to markets to strategize their proposals or to help to embed metrics for evaluation, feel free to email me.

This report that Farmers Market Coalition did with Market Umbrella in 2013 may be very useful for markets to review to see what other markets have done with their funding and to extract grant writing language used successfully by other markets and food systems.

Also, I am linking the report that I assisted the Real Food Gulf Coast folks with last year. They wanted to collect some simple data on how eaters and producers perceive markets (both those that use markets and don’t use them); the recommendations and marketing strategies will be piloted this year in Mississippi.

Please don’t be afraid to attempt a small grant if you have an idea to build capacity for a market or many markets. The assortment of grant opportunities is wider than ever before and can be the difference between struggling to stay relevant and moving a local food system to the next level.

AND please create an account on grants.gov sooner rather than later; this is the site you use for any federal grant so it takes a step from your later work when uploading a proposal as it takes some time to be approved for an account on grants dot gov.

Another detractor and another clear need for better data and reporting

For those of you who have read my “Big Data, Little Farmers Markets” blog posts linked here, and the Farmers Market Metrics pilots many of us have worked on, you know this is the kind of media that concerns me. I will fully agree that farmers markets have limits to their ability in carrying food equity on their shoulders, although I am not sure that markets ever promised that.

The findings extracted for this article lack necessary context and since the original academic article is behind a paywall, many are left to wonder how closely this piece extrapolated the best ideas from the study. However, I won’t be surprised if this small study did say exactly what has been used here, but I’d hope it made allowances for the small scope of the research and the lack of comparable metrics between community food systems and the industrial retail sector.

Farmers’ markets offered 26.4 fewer fresh produce items, on average, than stores.

Compared to stores, items sold at farmers’ markets were more expensive on average, “even for more commonplace and ‘conventional’ produce.”

Fully 32.8 percent of what farmers’ markets offered was not fresh produce at all, but refined or processed products such as jams, pies, cakes, and cookies.

As those of us know that are working constantly to expand the reach of good food, there has never been a belief among those that run markets that our role was to replace stores, especially the small stores and bodegas likely to be present in many of the boroughs of NYC. Instead, the lever of markets is meant to offer alternatives AND to influence traditional retail by changing everyone’s goals to include health and wealth measures that benefit regional producers, all eaters and the natural world around us.

As far as being more expensive, one might wonder if that the study did not compare the same quality of goods; these price comparisons often compare older produce with less shelf life to just-picked and carefully raised regional goods. I have bought much lettuce this year from a few of my neighboring markets that lasted 3-4 weeks in my refrigerator, which I have never been able to match with the conventional trucked-in produce seen in my lovely little stores that I frequent for many of the staples I need. Additionally, the price comparisons I have conducted or have seen have shown most market goods to be competitively priced or cheaper in season, so this study may need a larger data set or maybe a longer study period.

Generally speaking, refined or processed foods available from cottage producers at a market are markedly different from what is seen in the list of ingredients in most items on a grocery store shelf. Using fruit or vegetable seconds for fresh fruit spread or salsa is common among market vendors and extends the use of regional goods. And of course, balancing one’s diet means allowing for a treat on the table after that good dinner and may actually lead to less junk food later.

And finally, the article does not even consider the positive impacts found in markets for regional producers or neighborhood entrepreneurs; that omission in these type of articles is always a warning to me that we are reading an author who has spent little or no time quantifying the needs of the entire community being served in the market. If you require proof of the need to show the multiple impacts of farmers markets, the author’s curt conclusion should make that need clear:

Sure, they’re a great place to mingle. But as to whether they are a net nutritional plus for the neighborhood, the answer appears to be: Not so much.

(someone needs to introduce this guy to the idea of social determinants of health.)

Even so, as mentioned in those Big Data and FMM posts (a new Big Data post is coming soon), even these weak arguments are still based on data and analysis which means WE need to do a better job as well. It’s high time that we started to publish regular reports from the front lines of farmers markets, CSAs and other food and civic projects that use our own good data to show the impact that we are making everywhere rather than just keep rebutting these viral pieces that offer incomplete or inaccurate snapshots.

Mo’ Money? No Problem.

The picture is from my regular weekly, year-round Saturday market, founded in 1996 in the small town of Covington Louisiana, which is only 40 miles north of New Orleans but separated from it by Lake Pontchartrain and its 24 mile-long bridge.

The market is very ably run by sisters Jan and Ann, using very minimum staff hours but with enormous amounts of community buy-in. They have music scheduled every week, often have food trucks and during holidays have author signings or tasting events. The market has loads of seating, a permanent welcome structure with donated coffee and branded merchandise for sale. I tell you all of that to show how they balance the needs of the shoppers (by adding amenities that cannot be offered by the vendors) and the needs of their vendors (they keep the fees low by having less staff hours and carefully curate the products to showcase only high-quality regionally produced items), but also do their very best in their estimation to reduce their own wear and tear as staff.

To that end, they decided long ago to not participate in the same farmers market wireless machine/token system that we had in New Orleans; I had been the Deputy Director of that market organization and in 2006 or so had shared news of our emerging token and benefit program system with nearby markets in case they wanted to add the same; Covington told me then they didn’t see the need in their small town, even though they know and care about the large number of low-income people on benefit programs living nearby and do their best to offer a wide variety of price points and goods. I must confess that after our initial chat I was a bit disappointed by the lack of interest in expanding the reach, but soon realized this was an example of a particular type of market (rural niche) and the leadership was comfortable with the middle-class vibe they had certainly attracted. And I also realized a few years later that if they had been influenced by our complex system, it would have probably been a wrong move for the market at that time (more on that later.)

They knew, however, they at least needed the access for shoppers to get more cash and had asked the bank (a market sponsor) to have an ATM, and had also asked the municipality to add one (the market space is on city hall property), but couldn’t get anyone to move on the request. Finally, a 3rd party entrepreneur approached them to put one in and ta-daa, they finally have their ATM. It is moved in on Saturday morning and out again when the market is done, but the market will have a conversation soon with the mayor (a strong market supporter) about getting it there permanently. I was thrilled to see even that machine, as the nearest bank is blocks away and on far too many days I have grumpily got BACK in my truck to get more cash.

And in the days since those early rounds of proselytizing for (only) a centralized token/EBT/Debit system at every market, my own work has led me to the conclusion that instead there needs to be a suite of systems for markets to choose the appropriate version to process cards, rather than just the one system for everyone. Some markets can serve their shoppers with an ATM (some can own it, some can lease theirs and some can have a 3rd party offer the service like Covington), with some farmers having EBT/debit access on their own; some markets can use a phone-in system for EBT and have a Square on a smart phone at the market or farmer-level; some need the centralized system, but are figuring out electronic token systems; and yes, some do still need to bells and whistles of the centralized token system; and some markets need that system that is still developing, as technology continues to change to add more options for these systems.

What will help this multi-tiered system to happen is for markets to keep on sharing their ideas with each other and to gather data on why their system works for their community. That may be as simple as doing a regular Dot Survey/Bean Poll to ask shoppers about the interest in card use, or doing an annual economic survey like SEED, or asking their vendors on their annual renewal/application form about their use or projected use of card technology (you’d be surprised how many vendors already have Square or another version of it). And markets and vendors that do have the technology need to track the time and effort it takes to process cards and to build the entire system, which includes some outreach and marketing, and a significant amount of bookkeeping and share that information.

I keep gathering examples of innovation among markets and hope that sooner or later I (or other more able researchers) can be tasked with conducting in-depth research about those ideas to offer the market field a more comprehensive and dynamic view of all of the great ideas managed by our market systems. In the meantime, if you come to Covington your pajeon (warm Korean pancake) is on me; after all, I’ve got the cash.