In thousands of public actions, organizers and citizens are taking to the streets to demand transparency and community control over their police, and an acknowledgement of the structural racism that is built into every system that governs modern life, a structure that restricts black Americans and other people of color from participation in the economy, in civic decisions, and severely limits access to assets required to live a full, happy life.

But by dint of the work we chose, we get to do much more than that. By choosing to expand the role of local communities through mechanisms such as farmers markets, our intention to be part of a new equitable, community-led and transparent system is in the right place, even if the outcomes are still not where we want them to be. Because of that, farmers market leaders must vociferously acknowledge the rights of Americans to use public space for achieving equity for black lives and to clarify to their communities that the goal of our work is about building new systems rather than just propping up the old.

The 2 loops theory below is one way to describe the type of sweeping changes we are working towards, and even shows some of the steps:

When structural changes are the goal, it is important to know how living systems begin as networks, shift to intentional communities of practice, and can evolve into powerful systems capable of global influence. And that we live with the “old” and the “new” as it happens and that the existence of both at one time is often a point of tension but also allows us to free ourselves from worrying about achieving it all at once.

The process outlined in this video can assist farmers market leaders in understanding how to keep their goals to what is truly transformative.

As food leader Leah Penniman has outlined, education, reparations, and amplification are the strategies necessary for anti-racism work and as allies, we can lead in our own communities to expand those. This start (via the networks and CoP steps outlined above) requires that we shift from the white-led organizations that populate our work to one with diverse leadership, valuing both lived and professional experience, with information flowing back and forth between communities of practices within a new system for our markets and community food outlets to operate. (Please look for upcoming posts around what I find to share what farmers market operators are doing or can do in the anti-racism work that Ms. Penniman has helpfully outlined.)

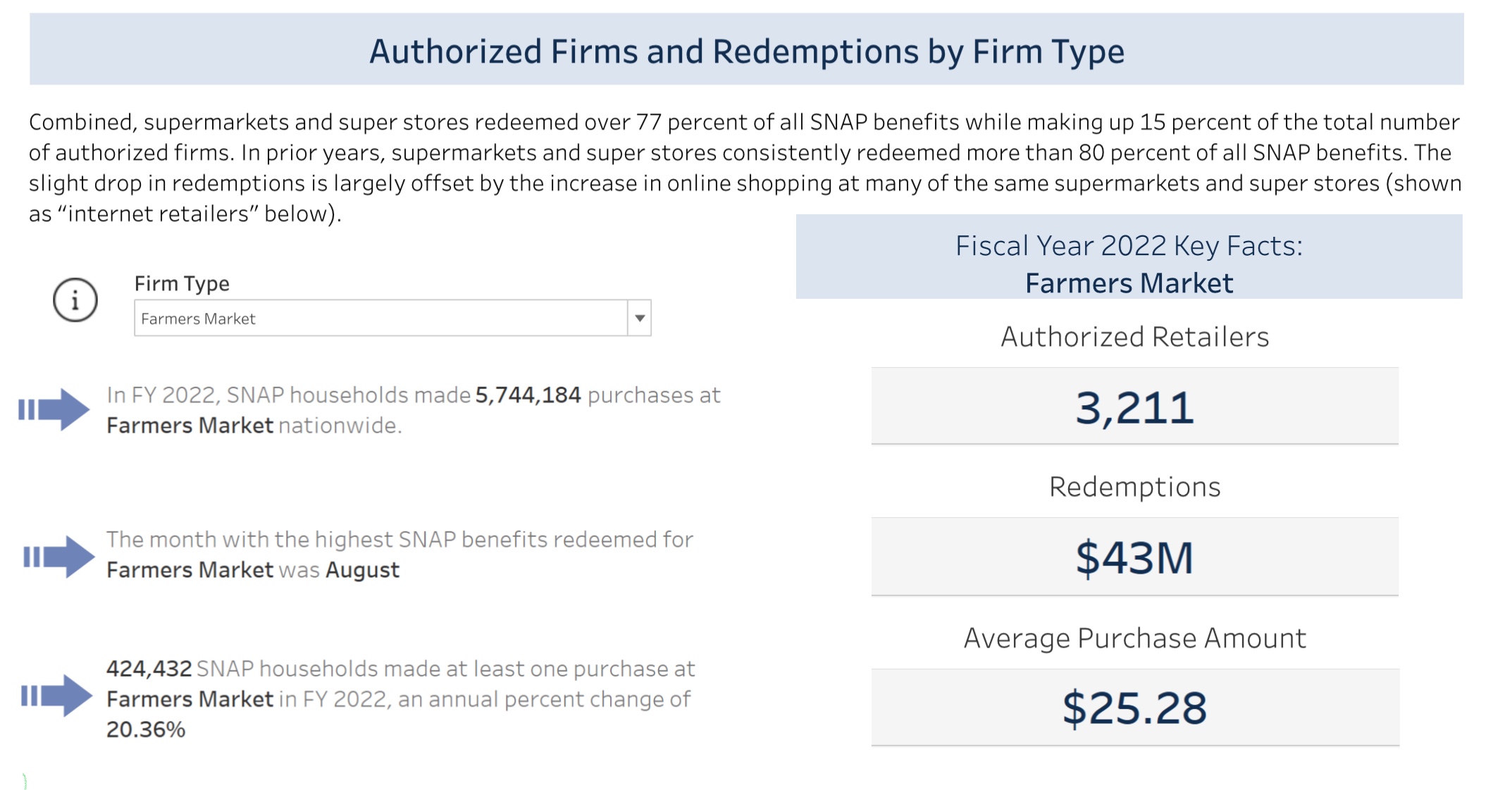

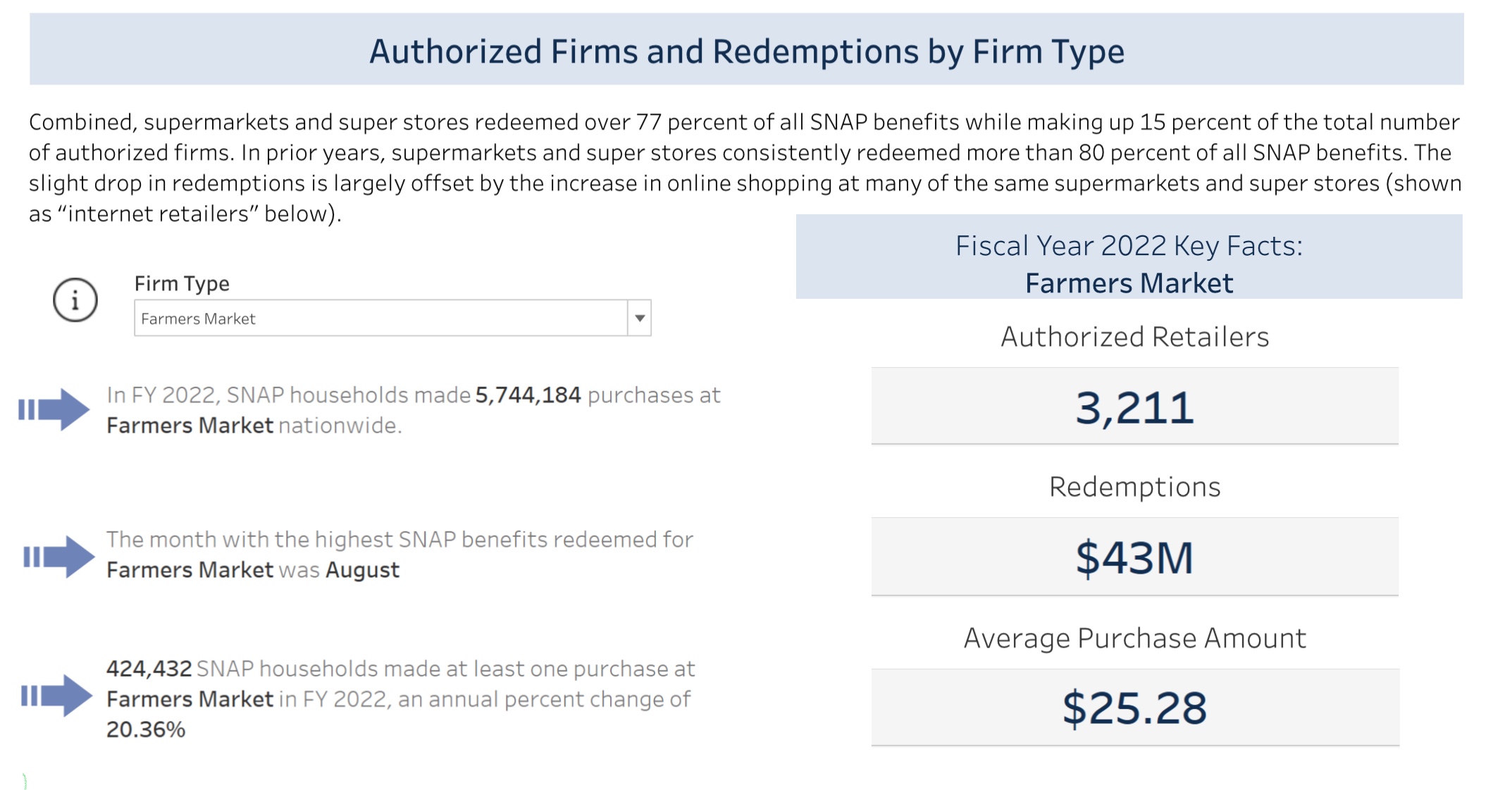

So I hope that actual structural change and plans for that change are the point of your organization’s (or work’s) theory of change. Start by acknowledging that most DTC leadership (such as my own employer Farmers Market Coalition) are still overwhelmingly white with little or no first-hand knowledge or personal experience in the daily reality of our black neighbors. That lack of experience and therefore of true understanding leads to many lost opportunities in our work including addressing the rapidly decreasing number of African-American farmers. Too often – far too often – the only way that DTC outlets address the racial inequities present in their spaces is by working on access for underserved and at-risk populations, by assuming that successful SNAP programs will accomplish what needs to be done. Don’t take that wrong- the work we have done in DTC outlets to increase access is tremendous work, but we have much more to do to attack the larger inequities that keep the old system purring right along.

I personally commit to full support of these goals by more actively working to eradicate the unacknowledged and unchallenged racism in our present system and to achieve my mid-term work goal to step down from holding leadership positions in order to become a better ally in the new system. And to openly share the knowledge and contacts I have collected over the years with the emerging diverse pool of leaders that represent the new wave of our work.

What are the organizational and the personal choices you will make to grow the networks and the new system? What uncomfortable truths will you commit to amplifying to your community to educate them to begin to shift power and assets to the black community?

I look forward to hearing more from many of you about your work in system change and how I can learn from it.

Canada’s long-awaited national food policy is getting $134.4 million over five years, on a cash basis, starting next year.

The plan will also see Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) oversee a new $50 million Local Food Infrastructure Fund, to be distributed over five years. The money will help fund and support “infrastructure for local food projects,” including at food banks, farmers’ markets and other community-driven projects.

ipolitics.ca/2019/03/19/budget-2019-canada-gets-a-national-food-policy/

The owners received a $1 million loan from the city’s Fresh Food Retailer Initiative, a program aimed at increasing residents’ access to fresh food. According to reports at the time, $500,000 of the loan was forgivable.

Seems to be a tragic confluence of bad-faith investments, management disorder, new disruptive businesses taking away some of the sales, and the lack of resilience in the city around its increasing environmental challenges. Still, I’d like to see what else this fund ended up supporting and what those places are doing now.

Some relevant quotes from Ian’s story linked below:

One of lenders that funded the store’s reopening was First NBC Bank, the local financial institution that collapsed last spring and continues to send ripples through the New Orleans business community. Boudreaux said his loan was acquired by another financial institution which has been more aggressive.

“We opened with the finances upside down to begin with, and it got worse,” he said.

The city also provided a $100,000 Economic Development Fund grant, and the Louisiana Office of Community Development provided a loan for $1 million. The store also received $2.2 million in historic tax credit equity and $2.2 million in new market tax credit equity.

Meanwhile, Boudreaux has accused some relatives of stealing money from the family-run business.

While these issues have been ongoing, Boudreaux pointed to the August 2017 flood as perhaps the last straw for the business. That disaster, spurred by a summer downpour that revealed widespread problems with the city’s drainage systems, swamped the store and knocked out much of its food-storage equipment.

Here’s my post on the first store closure that had been a recipient.

I mention Circle Food in this piece on another public market site:

Karen Weese is a freelance writer whose work has appeared in Salon, Dow Jones Investment Advisor, the Cincinnati Enquirer, Everyday Family, and other publications.

There are many prescriptions for combating poverty, but we can’t even get started unless we first examine our assumptions, and take the time to envision what the world feels like for families living in poverty every day.

My home market organization continues to pilot new ways to include at-risk populations into their community. The staff shared with me that they studied the Sustainable Food Center’s work in Austin TX with CVB to design their pilot. This mock program will lead the state into seeing how WIC families benefit from markets in terms of social and intellectual capital as well as increasing their regular access to healthy food.

(The article seems to state that CCFM has been doing SNAP redemptions since 2008; actually it has been accepting EBT cards to redeem SNAP benefits since 2005 and doing market matches on different programs since before then, including a seafood bucks program and a FMNP reward program for seniors to spend once they spent their FMNP coupons. The incentive added to SNAP has been a program in existence at the market since around 2008.)

Market Umbrella deserves credit for its continued innovation and the staff and board’s willingness to constantly explore ways to increase their markets’ reach.

Crescent City Farmers Market programs give free food to mothers | NOLA.com

The earlier proposals also recommended leaving food with multiple ingredients like frozen pizza or canned soup off the staple list. The outcome is a win for the makers of such products, like General Mills Inc. and Campbell Soup Co., which feared they would lose shelf space as retailers added new items to meet the requirements.

But retailers still criticized the new guidelines as too restrictive. Stores must now stock seven varieties of staples in each food category: meat, bread, dairy, and fruits and vegetables….

…More changes to the food-stamp program may lie ahead. The new rules were published a day after the House Committee on Agriculture released a report* calling for major changes to the program, which Republicans on the committee say discourages recipients from finding better-paid work.

Source: Regulators Tweak SNAP Rules for Grocers – WSJ

*Some of the findings from the 2016 Committee on Agriculture Report “Past, Present, and Future of SNAP” are below.

According to research by the AARP Foundation—a charitable affiliate of AARP—over 17 percent of adults over the age of 40 are food-insecure. Among age cohorts over age 50, food insecurity was worse for the 50-59 age group, with over 10 percent experiencing either low or very low food security. Among the 60-69 age cohort, over 9 percent experienced similar levels of food insecurity, and over 6 percent among the 70+ population.

• The operation of the program is at the discretion of each state. For instance, in California, SNAP is a county-run program. In Texas, SNAP is administered by the state… Dr. Angela Rachidi of the American Enterprise Institute cited a specific example in New York City where SNAP, WIC, school food programs, and child and adult care programs are all administered by different agencies and the result is that each agency must determine eligibility and administer benefits separately.

K. Michael Conaway, Chairman of the House Committee on Agriculture. Hearing of the House of Representatives, Committee on Agriculture. Past, Present, and Future of SNAP. February 25, 2015. Washington, D.C. Find report here

From CNN this week:

The number of people seeking emergency food assistance increased by an average of 2% in 2016, the United States Conference of Mayors said in its annual report Wednesday.

The majority, or 63%, of those seeking assistance were families, down from 67% a year ago, the survey found. However, the proportion of people who were employed and in need of food assistance rose sharply — increasing to 51% from 42%.

Shailene Woodley, Rosario Dawson, Will Smith and Kristen Bell are just a few of the big name stars teaming up with Thrive Market, a digital marketplace where individuals can purchase affordable, healthy food. They’re petitioning lawmakers and retailers to allow the use of food stamps online.

A report from the Hamilton Project highlights the lingering effects of the Great Recession on food insecurity…

There’s considerable state-by-state variation in food insecurity levels across the country, demonstrating once again that geography matters if you’re poor.

Here’s what Vilsack had to say about some states’ approach to the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, and whether SNAP should be eliminated in favor of a block grant (as House Speaker Paul Ryan has proposed):

I’m leery about block grants, just simply because I haven’t seen governors step up.

I alluded earlier, when we came in in 2009, there were states where a little over 50 percent of eligible people were actually receiving SNAP because that particular governor, that particular administration, did not care enough to make sure that people knew about these benefits, did not care enough to make sure that their bureaucracy was getting information out in languages that people could understand, did not care enough to simplify the process, so I’m skeptical.The Obama administration has successfully increased overall SNAP participation levels to 85 percent, but Vilsack’s comments illustrate how seemingly minor local political decisions around SNAP education and outreach can affect enrollment in a program that effectively reduces food insecurity.

The Link Between Food Insecurity and the Great Recession — Pacific Standard

Now he’s on a mission to feed the hungry in Central Indiana. Lawler has revamped his 36-acre farm into a nonprofit operation called Brandywine Creek Farms. His goal for the first year is to donate 500,000 pounds of food, which he said is realistic based on the farm’s capacity and the addition of an army of volunteers to help through the season.

On top of that, Lawler has joined forces with Gleaners, Midwest Food Bank, Kenneth Butler Soup Kitchen and other area food banks as distribution partners.

Farmer gives away harvest to feed hungry in his town

An example of social (bridging) and human (knowledge shared) capital impacts, designed and led by a farmer.

But though the need for seed banks is often associated with more stereotypically environmental, even futuristic, cataclysms (climate change; disease; pesticide-resistant insects) their history is inextricably tied up with something more banal and present-day—war.

…virtually no conflict has gone by without a devastating loss of seeds, often mitigated by a heroic rescue or underscored by a tragic attempt. Afghani mujahideen destroyed Kabul’s national seed collection in 1992. (Local scientists managed to smuggle some seeds into the basement of a few city houses, but by the time they returned to check on them a decade later, looters had dumped them on the floor in order to steal the storage jars.) During the Georgian civil unrest of 1993, just before the country’s Sukhumi Seed Station was destroyed, an 83-year-old botanist named Alexey Fogel escaped into the Caucasus Mountains with its entire lemon collection. Scientist Alexis Rumaziminsi, now known as the “bean boffin of Rwanda,” protected the many varieties of beans in his research plots during 1994’s civil war and genocide. The US-led invasion of Iraq resulted in the razing of the country’s national seed bank in Abu Ghraib—not to mention the implementation of American-style seed laws, which mean that if Iraqis want to buy new seeds, they will have to pay for yearly usage licenses.

Source: From WWII to Syria, How Seed Vaults Weather Wars | Atlas Obscura

Congratulations!

USDA is funding projects in 26 states for up to 4 years, using funds from FY2014 and FY2015. USDA will issue a separate request for applications in FY16, and in subsequent years. Fiscal year 2014 and 2015 awards are:

Pilot projects (up to $100,000, not to exceed 1 year):

Yolo County Department of Employment and Social Services, Woodland, Calif., $100,000

Heritage Ranch, Inc., Honaunau, Hawaii, $100,000

Backyard Harvest, Inc., Moscow, Idaho, $10,695

City of Aurora, Aurora, Ill., $30,000

Forsyth Farmers’ Market, Inc., Savannah, Ga., $50,000

Blue Grass Community Foundation, Lexington, Ky., $47,250

Lower Phalen Creek Project, Saint Paul, Minn., $45,230

Vermont Farm-to-School, Inc., Newport, V.T., $93,750

New Mexico Farmers Marketing Association, Santa Fe, N.M., $99,999

Santa Fe Community Foundation, Santa Fe, N.M., $100,000

Guilford County Department of Health and Human Services, Greensboro, N.C., $99,987

Chester County Food Bank, Exton, Pa., $76,543

Nurture Nature Center, Easton, Pa., $56,918

Rodale Institute, Kutztown, Pa., $46,442

Rhode Island Public Health Institute, Providence, R.I., $100,000

San Antonio Food Bank, San Antonio, Texas, $100,000

Multi-year community-based projects (up to $500,000, not to exceed 4 years):

Mandela Marketplace, Inc., Oakland, Calif., $422,500

Market Umbrella, New Orleans, La., $378,326

Maine Farmland Trust, Belfast, Maine, $249,816

Farmers Market Fund, Portland, Ore., $499,172

The Food Trust, Philadelphia, Pa., $500,000

Utahns Against Hunger, Salt Lake City, Utah, $247,038

Opportunity Council, Bellingham, Wash., $301,658

Multi-year large-scale projects ($500,000 or greater, not to exceed 4 years):

Ecology Center, Berkeley, Calif., $3,704,287

Wholesome Wave Foundation Charitable Ventures, Inc., Bridgeport, Conn., $3,775,700

AARP Foundation, Washington, D.C., $3,306,224

Florida Certified Organic Growers and Consumers, Gainesville, Fla., $1,937,179

Massachusetts Department of Transitional Assistance, Boston, Mass., $3,401,384

Fair Food Network, Ann Arbor, Mich., $5,171,779

International Rescue Committee, Inc., New York, N.Y., $564,231

Washington State Department of Health, Tumwater, Wash., $5,859,307

Descriptions of the funded projects are available on the NIFA website.

This is an excellent snapshot of some of Canada’s work to deal with food insecurity as well as a short list of some great actions being taken to expand past emergency food to assert food sovereignty and skills such as seed-saving, foraging and many others. Glad to see Food Share and The Stop in here- two Ontario groups that I admire greatly and watch closely for ideas to bring to the U.S.

Eight stories that will give you food for thought

Food insecurity, which has only been measured specifically and consistently on the Canadian Community Health Survey since 2005, can mean a sliding scale from worrying about next week’s grocery budget, to buying mostly canned goods instead of pricier milk and vegetables, to skipping meals entirely. All three scenarios are a problem; the latter two have significant health consequences.

Breaking bread in a hungry world – The United Church Observer.

As we move into another year of organizing around regional food and public health in the US, we are facing opposition that has become stronger and more agile at pointing out our weaknesses and adding barriers to those that we already have to erase. That opposition can be found in our towns, at the state legislature, in Congress and even among our fellow citizens who haven’t seen the benefits of healthy local food for themselves yet.

That opposition uses arguments of affordability without measuring that fairly against seasonality or production costs, adds up the energy to get food to local markets while ignoring the huge benefits of farming small plots sustainably, shrugs its shoulders at stories of small victories, pointing past them to large stores taking up space next to off ramps and asks isn’t bigger better for everyone?

Why the opposition to local producers offering their goods to their neighbors, their schools and stores? What would happen to the society as a whole if our projects were allowed to exist and to flourish alongside of the larger industrial system?

I would suggest that very little would change, at least at first. Later on-if we continue to grow our work-it may be another matter and this fear of later is at the core of the opposition. That fear has to do with the day that democratic systems become the norm and necessary information is in the hands of eaters, farmers and organizers. And so we need to address and keep on addressing the divide that keeps that from happening.

The truth that we all know is that there is already two systems-one for the top percent and another for the rest. Writer George Packer gave his framework for this very argument in an eloquent essay written in 2011 called “The Broken Contract.” Packer argues that the divide in America began to take hold in 1978 with the passage of new laws that allowed organized money to influence elected officials in ways not seen before.

Packer points out that the access to Congress meant that labor and owners were not sitting down and working together any longer. That large corporations stopped caring about being good citizens and of supporting the social institutions and turned their entire attention to buying access in Congress and growing their profits and systems beyond any normal levels.

“The surface of life has greatly improved, at least for educated, reasonably comfortable people—say, the top 20 percent, socioeconomically. Yet the deeper structures, the institutions that underpin a healthy democratic society, have fallen into a state of decadence. We have all the information in the universe at our fingertips, while our most basic problems go unsolved year after year: climate change, income inequality, wage stagnation, national debt, immigration, falling educational achievement, deteriorating infrastructure, declining news standards. All around, we see dazzling technological change, but no progress…

…We can upgrade our iPhones, but we can’t fix our roads and bridges. We invented broadband, but we can’t extend it to 35 percent of the public. We can get 300 television channels on the iPad, but in the past decade 20 newspapers closed down all their foreign bureaus. We have touch-screen voting machines, but last year just 40 percent of registered voters turned out, and our political system is more polarized, more choked with its own bile, than at any time since the Civil War.

…when did this start to happen? Any time frame has an element of arbitrariness, and also contains the beginning of a theory. Mine goes back to that shabby, forgettable year of 1978. It is surprising to say that in or around 1978, American life changed—and changed dramatically. It was, like this moment, a time of widespread pessimism—high inflation, high unemployment, high gas prices. And the country reacted to its sense of decline by moving away from the social arrangement that had been in place since the 1930s and 1940s.

What was that arrangement? It is sometimes called “the mixed economy”; the term I prefer is “middle-class democracy.” It was an unwritten social contract among labor, business, and government— between the elites and the masses. It guaranteed that the benefits of the economic growth following World War II were distributed more widely, and with more shared prosperity, than at any time in human history……The persistence of this trend toward greater inequality over the past 30 years suggests a kind of feedback loop that cannot be broken by the usual political means. The more wealth accumulates in a few hands at the top, the more influence and favor the well-connected rich acquire, which makes it easier for them and their political allies to cast off restraint without paying a social price. That, in turn, frees them up to amass more money, until cause and effect become impossible to distinguish. Nothing seems to slow this process down—not wars, not technology, not a recession, not a historic election.

The economic divide and the lack of information about it hurts our movement since many still see us as either too small or too elitist and so delays our work getting to more people that need it. I urge everyone to find a copy of this entire essay and share it and discuss it widely.