Oh the fires. It’s terrifying to watch them unfold especially viewing from videos taken with hand-held phones with calm narration from the very folks who are seeing their place burn up.

There has been natural (and unnatural) disasters in my own place more than once and so I have a bit of an out of body sensation watching those videos, having made a few myself. Soon will come the overwhelming finality of knowing how many beings have been lost, how many have lost home, how long it will take just to not see or smell the destruction. (I remember driving through Montpelier VT after their devastating flood not that long ago, smelling the musty items out on the curb to be tossed in the trash, and how the years-old Katrina memories came rushing back.)

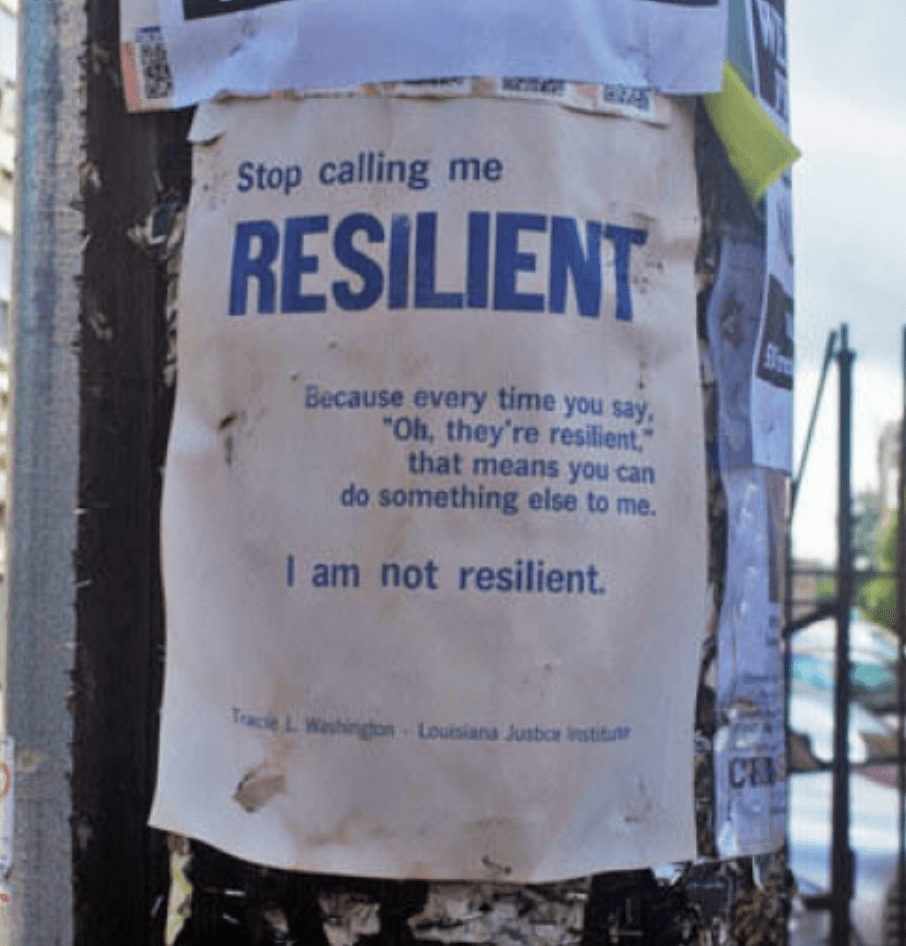

Once the people are back, there will be a period of exuberance when they are able to stand there, to see each other, and to talk it out. That period lasts for a few months while more come back, while they clean out their places…Then it’s on to other phases, some less pleasant, all of which last years and are much longer lasting than the attention from media or even the kind questions from folks from other places.

I must confess that I only realized a few years back that I have yet to “land” anywhere since the loss of my place in 2005, and have come to see that I cannot seem to trust in the idea of a constant home yet. Instead, I do my best to make that home in many places, and to find small comforts that travel with me.

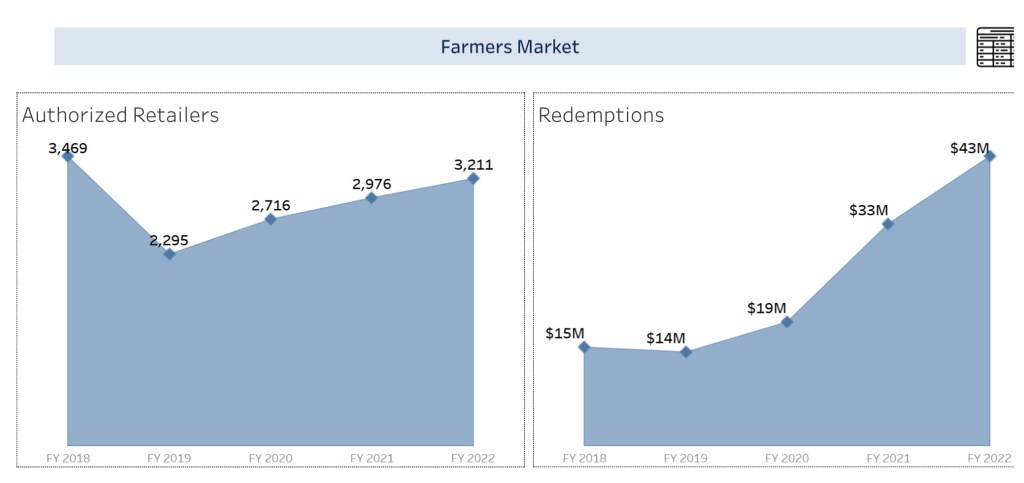

And yes since this is a blog for market communities, I gratefully include those markets as spaces where I feel less alone, less “on the road.” But its not just the market spaces; it’s also the community of market people who call or email or meet up with me to spend a few minutes or longer, recounting recent experiences or pulling out a shared memory to laugh or to mourn over or ask for my update, listening attentively while I do.

That is the real magic of this work we do: that we create comfort and belonging which doesn’t always live in a physical space, but is carried by a shared belief that showing up, by seeing people as more valuable than just the sum of their transactional history, by pushing against the cynicism of faster and cheaper as better, by looking people in the eye to ask how they are and waiting for an answer, by including everyone, we belong to the comforting.

Our friends in Los Angeles will need that, just as friends everywhere who have lost already have needed that.

That is a huge part of why the work we do is constantly vital even when the markets are closed and market leaders are back to their planning, and our producers are back on the land, and in their kitchens with their recipes and in their fields with their animals…

Sustained community. That’s the magic.